Law of comparative judgment

The law of comparative judgment was conceived by L. L. Thurstone. In modern day terminology, it is more aptly described as a model that is used to obtain measurements from any process of pairwise comparison. Examples of such processes are the comparison of perceived intensity of physical stimuli, such as the weights of objects, and comparisons of the extremity of an attitude expressed within statements, such as statements about capital punishment. The measurements represent how we perceive objects, rather than being measurements of actual physical properties. This kind of measurement is the focus of psychometrics and psychophysics.

In somewhat more technical terms, the law of comparative judgment is a mathematical representation of a discriminal process, which is any process in which a comparison is made between pairs of a collection of entities with respect to magnitudes of an attribute, trait, attitude, and so on. The theoretical basis for the model is closely related to item response theory and the theory underlying the Rasch model, which are used in Psychology and Education to analyse data from questionnaires and tests.

Contents |

Background

Thurstone published a paper on the law of comparative judgment in 1927. In this paper he introduced the underlying concept of a psychological continuum for a particular 'project in measurement' involving the comparison between a series of stimuli, such as weights and handwriting specimens, in pairs. He soon extended the domain of application of the law of comparative judgment to things that have no obvious physical counterpart, such as attitudes and values (Thurstone, 1929). For example, in one experiment, people compared statements about capital punishment to judge which of each pair expressed a stronger positive (or negative) attitude.

The essential idea behind Thurstone's process and model is that it can be used to scale a collection of stimuli based on simple comparisons between stimuli two at a time: that is, based on a series of pairwise comparisons. For example, suppose that someone wishes to measure the perceived weights of a series of five objects of varying masses. By having people compare the weights of the objects in pairs, data can be obtained and the law of comparative judgment applied to estimate scale values of the perceived weights. This is the perceptual counterpart to the physical weight of the objects. That is, the scale represents how heavy people perceive the objects to be based on the comparisons.

Although Thurstone referred to it as a law, as stated above, in terms of modern psychometric theory the 'law' of comparative judgment is more aptly described as a measurement model. It represents a general theoretical model which, applied in a particular empirical context, constitutes a scientific hypothesis regarding the outcomes of comparisons between some collection of objects. If data agree with the model, it is possible to produce a scale from the data.

Relationships to pre-existing psychophysical theory

Thurstone showed that in terms of his conceptual framework, Weber's law and the so-called Weber-Fechner law, which are generally regarded as one and the same, are independent, in the sense that one may be applicable but not the other to a given collection of experimental data. In particular, Thurstone showed that if Fechner's law applies and the discriminal dispersions associated with stimuli are constant (as in Case 5 of the LCJ outlined below), then Weber's law will also be verified. He considered that the Weber-Fechner law and the LCJ both involve a linear measurement on a psychological continuum whereas Weber's law does not.

Weber's law essentially states that how much people perceive physical stimuli to change depends on how big a stimulus is. For example, if someone compares a light object of 1 kg with one slightly heavier, they can notice a relatively small difference, perhaps when the second object is 1.2 kg. On the other hand, if someone compares a heavy object of 30 kg with a second, the second must be quite a bit larger for a person to notice the difference, perhaps when the second object is 36 kg. People tend to perceive differences that are proportional to the size rather than always noticing a specific difference irrespective of the size. The same applies to brightness, pressure, warmth, loudness and so on.

Thurstone stated Weber's law as follows: "The stimulus increase which is correctly discriminated in any specified proportion of attempts (except 0 and 100 per cent) is a constant fraction of the stimulus magnitude" (Thurstone, 1959, p. 61). He considered that Weber's law said nothing directly about sensation intensities at all. In terms of Thurstone's conceptual framework, the association posited between perceived stimulus intensity and the physical magnitude of the stimulus in the Weber-Fechner law will only hold when Weber's law holds and the just noticeable difference (JND) is treated as a unit of measurement. Importantly, this is not simply given a priori (Michell, 1997, p. 355), as is implied by purely mathematical derivations of the one law from the other. It is, rather, an empirical question whether measurements have been obtained; one which requires justification through the process of stating and testing a well-defined hypothesis in order to ascertain whether specific theoretical criteria for measurement have been satisfied. Some of the relevant criteria were articulated by Thurstone, in a preliminary fashion, including what he termed the additivity criterion. Accordingly, from the point of view of Thurstone's approach, treating the JND as a unit is justifiable provided only that the discriminal dispersions are uniform for all stimuli considered in a given experimental context. Similar issues are associated with Stevens' power law.

In addition, Thurstone employed the approach to clarify other similarities and differences between Weber's law, the Weber-Fechner law, and the LCJ. An important clarification is that the LCJ does not necessarily involve a physical stimulus, whereas the other 'laws' do. Another key difference is that Weber's law and the LCJ involve proportions of comparisons in which one stimulus is judged greater than another whereas the so-called Weber-Fechner law does not.

The general form of the law of comparative judgment

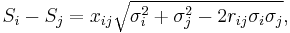

The most general form of the LCJ is

in which:

is the psychological scale value of stimuli i

is the psychological scale value of stimuli i is the sigma corresponding with the proportion of occasions on which the magnitude of stimulus i is judged to exceed the magnitude of stimulus j

is the sigma corresponding with the proportion of occasions on which the magnitude of stimulus i is judged to exceed the magnitude of stimulus j is the discriminal dispersion of a stimulus

is the discriminal dispersion of a stimulus

is the correlation between the discriminal deviations of stimuli i and j

is the correlation between the discriminal deviations of stimuli i and j

The discriminal dispersion of a stimulus i is the dispersion of fluctuations of the discriminal process for a uniform repeated stimulus, denoted  , where

, where  represents the mode of such values. Thurstone (1959, p. 20) used the term discriminal process to refer to the "psychological values of psychophysics"; that is, the values on a psychological continuum associated with a given stimulus.

represents the mode of such values. Thurstone (1959, p. 20) used the term discriminal process to refer to the "psychological values of psychophysics"; that is, the values on a psychological continuum associated with a given stimulus.

Case 5 of the law of comparative judgment

Thurstone specified five particular cases of the 'law', or measurement model. An important case of the model is Case 5, in which the discriminal dispersions are specified to be uniform and uncorrelated. This form of the model can be represented as follows:

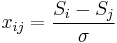

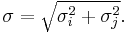

where

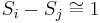

In this case of the model, the difference  can be inferred directly from the proportion of instances in which j is judged greater than i if it is hypothesised that

can be inferred directly from the proportion of instances in which j is judged greater than i if it is hypothesised that  is distributed according to some density function, such as the normal distribution or logistic function. In order to do so, it is necessary to let

is distributed according to some density function, such as the normal distribution or logistic function. In order to do so, it is necessary to let  , which is in effect an arbitrary choice of the unit of measurement. Letting

, which is in effect an arbitrary choice of the unit of measurement. Letting  be the proportion of occasions on which i is judged greater than j, if, for example,

be the proportion of occasions on which i is judged greater than j, if, for example,  and it is hypothesised that

and it is hypothesised that  is normally distributed, then it would be inferred that

is normally distributed, then it would be inferred that  .

.

When a simple logistic function is employed instead of the normal density function, then the model has the structure of the Bradley-Terry-Luce model (BTL model) (Bradley & Terry, 1952; Luce, 1959). In turn, the Rasch model for dichotomous data (Rasch, 1960/1980) is identical to the BTL model after the person parameter of the Rasch model has been eliminated, as is achieved through statistical conditioning during the process of Conditional Maximum Likelihood estimation. With this in mind, the specification of uniform discriminal dispersions is equivalent to the requirement of parallel Item Characteristic Curves (ICCs) in the Rasch model. Accordingly, as shown by Andrich (1978), the Rasch model should, in principle, yield essentially the same results as those obtained from a Thurstone scale. Like the Rasch model, when applied in a given empirical context, Case 5 of the LCJ constitutes a mathematized hypothesis which embodies theoretical criteria for measurement.

Applications

One important application involving the law of comparative judgment is the widely-used Analytic Hierarchy Process, a structured technique for helping people deal with complex decisions. It uses pairwise comparisons of tangible and intangible factors to construct ratio scales that are useful in making important decisions.[1][2]

References

- ^ Saaty, Thomas L. (1999-05-01). Decision Making for Leaders: The Analytic Hierarchy Process for Decisions in a Complex World. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: RWS Publications. ISBN 0-9620317-8-X. http://www.amazon.com/dp/096203178X.

- ^ Saaty, Thomas L. (2008-06). "Relative Measurement and its Generalization in Decision Making: Why Pairwise Comparisons are Central in Mathematics for the Measurement of Intangible Factors - The Analytic Hierarchy/Network Process". RACSAM (Review of the Royal Spanish Academy of Sciences, Series A, Mathematics) 102 (2): 251–318. http://www.rac.es/ficheros/doc/00576.PDF. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- Andrich, D. (1978b). Relationships between the Thurstone and Rasch approaches to item scaling. Applied Psychological Measurement, 2, 449-460.

- Bradley, R.A. and Terry, M.E. (1952). Rank analysis of incomplete block designs, I. the method of paired comparisons. Biometrika, 39, 324-345.

- Krus, D.J., & Kennedy, P.H. (1977) Normal scaling of dominance matrices: The domain-referenced model. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 37, 189-193 (Request reprint).

- Luce, R.D. (1959). Individual Choice Behaviours: A Theoretical Analysis. New York: J. Wiley.

- Michell, J. (1997). Quantitative science and the definition of measurement in psychology. British Journal of Psychology, 88, 355-383.

- Rasch, G. (1960/1980). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. (Copenhagen, Danish Institute for Educational Research), expanded edition (1980) with foreword and afterword by B.D. Wright. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Thurstone, L.L. (1927). A law of comparative judgement. Psychological Review, 34, 273-286.

- Thurstone, L.L. (1929). The Measurement of Psychological Value. In T.V. Smith and W.K. Wright (Eds.), Essays in Philosophy by Seventeen Doctors of Philosophy of the University of Chicago. Chicago: Open Court.

- Thurstone, L.L. (1959). The Measurement of Values. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.